Alberto Kalach: Panorama

Alberto Kalach

August 3 – October 6, 2024

DOWNLOAD EXHIBITION MAP

“A hermit’s hut by the sea made with order and precision.” That’s how Mexican architect Alberto Kalach (b. 1960) describes a casita he built for his family on the beach in Oaxaca. Enclosing as little space as possible, it is a manifesto on the inadvisability of seeking luxurious insulation at the expense of our experience of the environment of our existence. Shelter, if it means sequestration from the world, is not the prime directive of architecture, it says. Removing barriers not erecting them is the mission: to connect us with ourselves, each other, and the world, rather than propounding and fulfilling false premises of complete comfort and perfect security. The program for a beach shack is, in short, the most direct possible experience of the beach—and all of the empirical, life-affirming goodness it entails.

In Kalach’s conception, architecture is a form of ethics, not just a functional and aesthetic vocation. “I don’t believe in testing forms per se,” he says, “but rather in ways of inhabiting, ways of building, ways of relating to nature.” By way of further explanation, Kalach often cites a mantra of the great Spanish architect José Maria Buendia (1933—2016) that “beauty begets beauty.” The purpose of creating beautiful environments—house, city, nation—being to inspire beautiful behavior. So, although his architecture is not explicitly spiritual, for Kalach its practice carries an inescapable moral urgency. When explaining why he removed the garage from a house he was renovating, for example, he said it was because “it seems to me a sin to stick a car in your sanctuary.” In his ideal republic every structure seeks and serves a sacred purpose and therefore merits the same spirit of craft and care that would go into building a cathedral, or one’s own home.

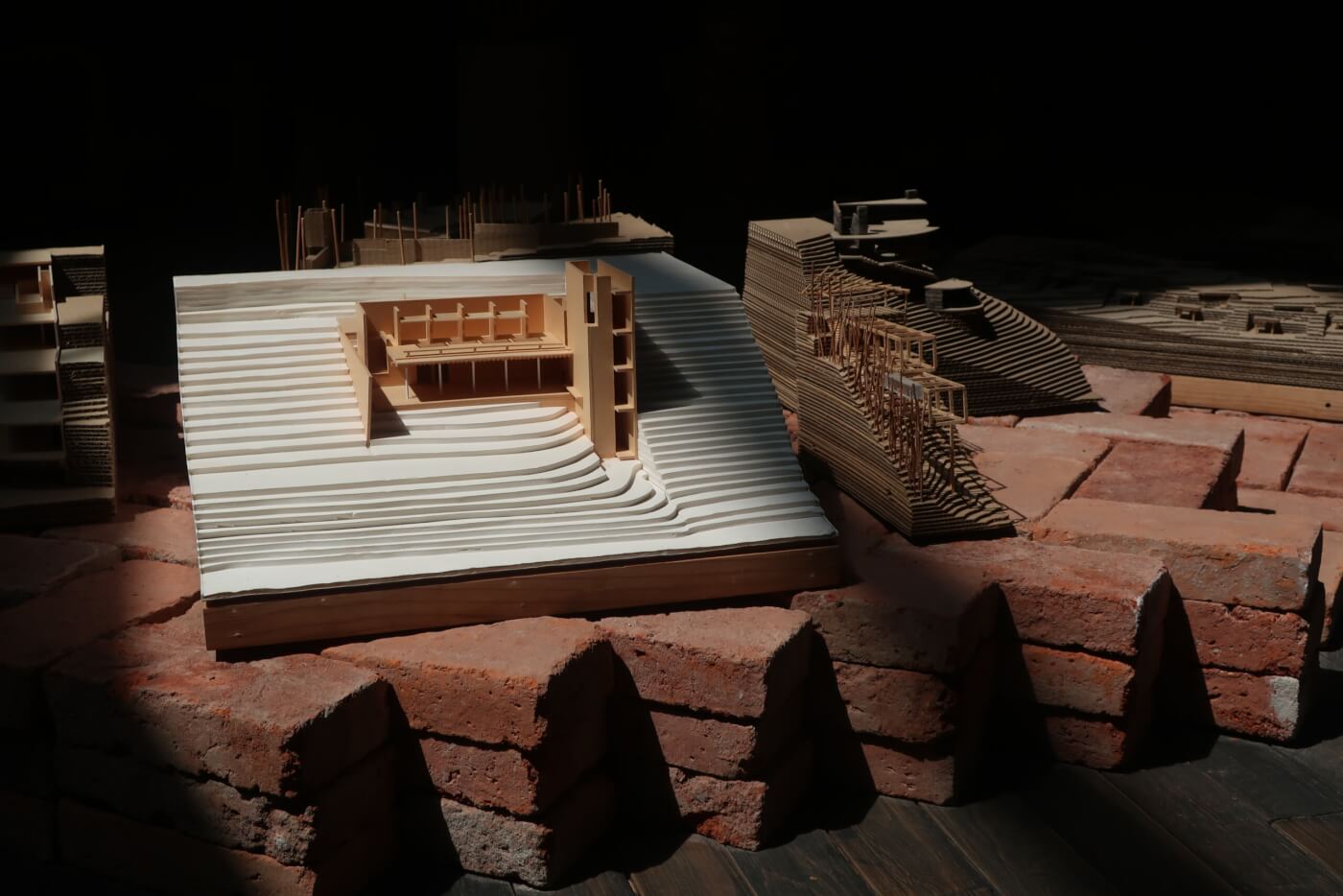

The panorama of México we have constructed here, in models of varying styles, scales, and levels of finish, represents a broad cross-section of Kalach’s thinking. His models are conceptual contracts he makes with the site and the client more than the usual promotional devices an architect makes to sell (or promote) a project. The selection encompasses everything from private homes and commercial buildings to master plans for public spaces, including his Quixotean, two-decade-long crusade to restore the lacustrine ecosystem of the valley of México. What stands out when looking at so many of these models together in the form of the nation are his unwavering sense of civic purpose and his determination to build at any scale with intimacy and openness. The goal is not starchitecture. Kalach is committed to discovering what might be accomplished by a skyscraper, a library, an airport, or a hospital made with the same simple sense of rightness and connection as his shack on the beach.

It’s not easy to be an idealist, in any field. In architecture the idealists tend to be the visionaries and futurists more comfortable with the righteous clarity of dreams than the messy processes associated with building. But Kalach is something else entirely. A throwback rebel, his work is marked by assertions of common sense drawn from tradition. He returns again and again to time tested truths. A house is better with a garden. A building should be sited and designed to keep its inhabitants cool, or warm, as local conditions dictate. The buildable space on a given piece of land should be allocated to do the most good for the community of its inhabitants. And because if anything can save the world, it is vegetation, not only is the garden non-negotiable, it deserves as much space as can conceivably be allocated to it.

If in Kalach architecture has its Martin Luther, these models are his theses, and this México is his existential reformation.

Dakin Hart

Artistic Director

OBJECT LIST

“A hermit’s hut by the sea made with order and precision.” That’s how Mexican architect Alberto Kalach (b. 1960) describes a casita he built for his family on the beach in Oaxaca. Enclosing as little space as possible, it is a manifesto on the inadvisability of seeking luxurious insulation at the expense of our experience of the environment of our existence. Shelter, if it means sequestration from the world, is not the prime directive of architecture, it says. Removing barriers not erecting them is the mission: to connect us with ourselves, each other, and the world, rather than propounding and fulfilling false premises of complete comfort and perfect security. The program for a beach shack is, in short, the most direct possible experience of the beach—and all of the empirical, life-affirming goodness it entails.

In Kalach’s conception, architecture is a form of ethics, not just a functional and aesthetic vocation. “I don’t believe in testing forms per se,” he says, “but rather in ways of inhabiting, ways of building, ways of relating to nature.” By way of further explanation, Kalach often cites a mantra of the great Spanish architect José Maria Buendia (1933—2016) that “beauty begets beauty.” The purpose of creating beautiful environments—house, city, nation—being to inspire beautiful behavior. So, although his architecture is not explicitly spiritual, for Kalach its practice carries an inescapable moral urgency. When explaining why he removed the garage from a house he was renovating, for example, he said it was because “it seems to me a sin to stick a car in your sanctuary.” In his ideal republic every structure seeks and serves a sacred purpose and therefore merits the same spirit of craft and care that would go into building a cathedral, or one’s own home.

The panorama of México we have constructed here, in models of varying styles, scales, and levels of finish, represents a broad cross-section of Kalach’s thinking. His models are conceptual contracts he makes with the site and the client more than the usual promotional devices an architect makes to sell (or promote) a project. The selection encompasses everything from private homes and commercial buildings to master plans for public spaces, including his Quixotean, two-decade-long crusade to restore the lacustrine ecosystem of the valley of México. What stands out when looking at so many of these models together in the form of the nation are his unwavering sense of civic purpose and his determination to build at any scale with intimacy and openness. The goal is not starchitecture. Kalach is committed to discovering what might be accomplished by a skyscraper, a library, an airport, or a hospital made with the same simple sense of rightness and connection as his shack on the beach.

It’s not easy to be an idealist, in any field. In architecture the idealists tend to be the visionaries and futurists more comfortable with the righteous clarity of dreams than the messy processes associated with building. But Kalach is something else entirely. A throwback rebel, his work is marked by assertions of common sense drawn from tradition. He returns again and again to time tested truths. A house is better with a garden. A building should be sited and designed to keep its inhabitants cool, or warm, as local conditions dictate. The buildable space on a given piece of land should be allocated to do the most good for the community of its inhabitants. And because if anything can save the world, it is vegetation, not only is the garden non-negotiable, it deserves as much space as can conceivably be allocated to it.

If in Kalach architecture has its Martin Luther, these models are his theses, and this México is his existential reformation.

Dakin Hart

Artistic Director

OBJECT LIST