El pasado nunca es el mismo

Jose Dávila

February 3, 2024 – January 6, 2025

Casa Wabi Puerto Escondido

Jose Dávila (b. 1974, Mexico) is best-known for balancing acts of commonplace materials that poignantly suggest the interpersonal entanglements and networks of dependence that constitute society. And with these, reflecting his own deep idealism and optimism, he makes obliquely eloquent arguments for the maintenance and care of those networks. Further, these balancing acts tend to make us feel that investing our awareness in webs of contingency and fragility is virtuous, even heroic. In El pasado nunca es el mismo, his site-specific exhibition for Casa Wabi, using nothing more than construction-site refuse collected from all over Puerto Escondido and a concept called collective memory, Dávila has set out to make concrete an idea of honoring the past and inhabiting history very different from the way that monuments have traditionally commemorated people and events.

By accessing and manipulating memory through mundane construction materials—the current material franca of civilization—the works he has made for Casa Wabi generate a sense of communality. Not only because refuse everywhere looks much the same, but because today most human beings share the anxiety that stems from living in environments in a perpetual state of building and unbuilding. A pile of rock—to take an example that has changed little in many millennia—is a universally evocative metaphor of collective understanding because rock is so basic to our experience of the built environment. And just as rock can be almost endlessly reincorporated into new structures, so we are constantly reconfiguring our memories: drawn from our own experience, but also the experiences of those around us, and from our cultures and histories, into a continuously renovated social structure. Plywood, reinforced concrete, and rebar have, similarly, become inescapable parts of this terroir of modern life—trash that represents us all: a kind of repository of common experience.

The French philosopher and sociologist Maurice Halbwachs (1877–1945), one of the early theorists of collective memory, was good at suggesting how our delusions of separation and self-sufficiency might come to riddle the prescriptions and presentation of history. Because so much of what we experience, or think of, as the uniqueness of ourselves actually expresses the combined influence of the many groups of which we are members.

A personal state thus reveals the complexity of the combination that was its source. Its apparent unity is explained by a quite natural type of illusion. Philosophers have shown that the feeling of liberty may be explained by the multiplicity of causal series that combine to produce an action. We conceive each influence as being opposed by some other and thus believe we act independently of each influence since we do not act under the exclusive power of any one. We do not perceive that our act really results from their action in concert, that our act is always governed by the law of causality. Similarly, since the remembrance reappears, owing to the interweaving of several series of collective thoughts, and since we cannot attribute it to any single one, we imagine it independent and contrast its unity to their multiplicity. We might as well assume that a heavy object, suspended in air by means of a number of very thin and interlaced wires, actually rests in the void where it holds itself up….

Halbwachs does not say so explicitly, but one logical extension of this thinking is that collective memory is the seedbed of our sense of collective responsibility to each other and to our world. That is the source of much of Dávila’s interest in the idea.

For Casa Wabi Dávila has created works that are more settled, stable, and centered than his characteristic heavy objects suspended in the void. In a relaxed, spontaneous, and collaborative process not unlike the stockpiling of materials for later use, he has arranged: rebar and sheet steel; sections of the plywood and steel formwork used to cast concrete; rocks; and sections of scaffolding and I-beams, in four separate rough, large, open boxes on the floor. The boxes, recalling the empty geometries of minimalism, here serve as containers: post-industrial brain cases of a sort, filled with the gray matter of material history. Where his cantilevered, strapped, and suspended sculptures epitomize the vast and somewhat terrifying potential energy in social systems, these works are more like batteries or solid state drives, in which collective experience is stored. Also significant in these works is the way that entropy and decay, in returning them to a lower natural state, seems to have renewed them, rendering them ready for reuse. Their “chromatics,” as Dávila puts it, have thus come to “seem endemic” to Casa Wabi and this part of Oaxaca. Which is to say that if these materials represent a condition of shared memory, that condition now includes the environment as well.

Against one wall of the gallery are stacked sheets of plywood left over from, among other uses, the production of the cement pedestals in the exhibition. Arranged as they are, by the unconscious logic of temporary storage, they have a casual resemblance to a rough city skyline in silhouette. Or individuals in perspective-flattened queues. The pedestals, made to Dávila’s studio’s specifications for the display of sculptures, are outside on the terrace—arranged as sculpture. When he arrived to make the exhibition, Dávila treated them like the rest of the discarded materials that had been gathered for his use and pulled them into the flow of recycling and renewal that produced the art that is the exhibition. By placing them alone outside, as if they were sculpture, Dávila has opened up their status by inviting them to try something else and by giving nature the opportunity to turn them from (manmade) stone into rocks. It’s an accelerated, art-specific experiment in what has already happened to the materials shown inside. The gesture is typical of the universalizing culture of care Dávila tends to cultivate. The manmade materials expended outside come in to rest and recharge; those made for use inside go out for the same reason. It’s a lovely, non-binary exchange without judgment: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

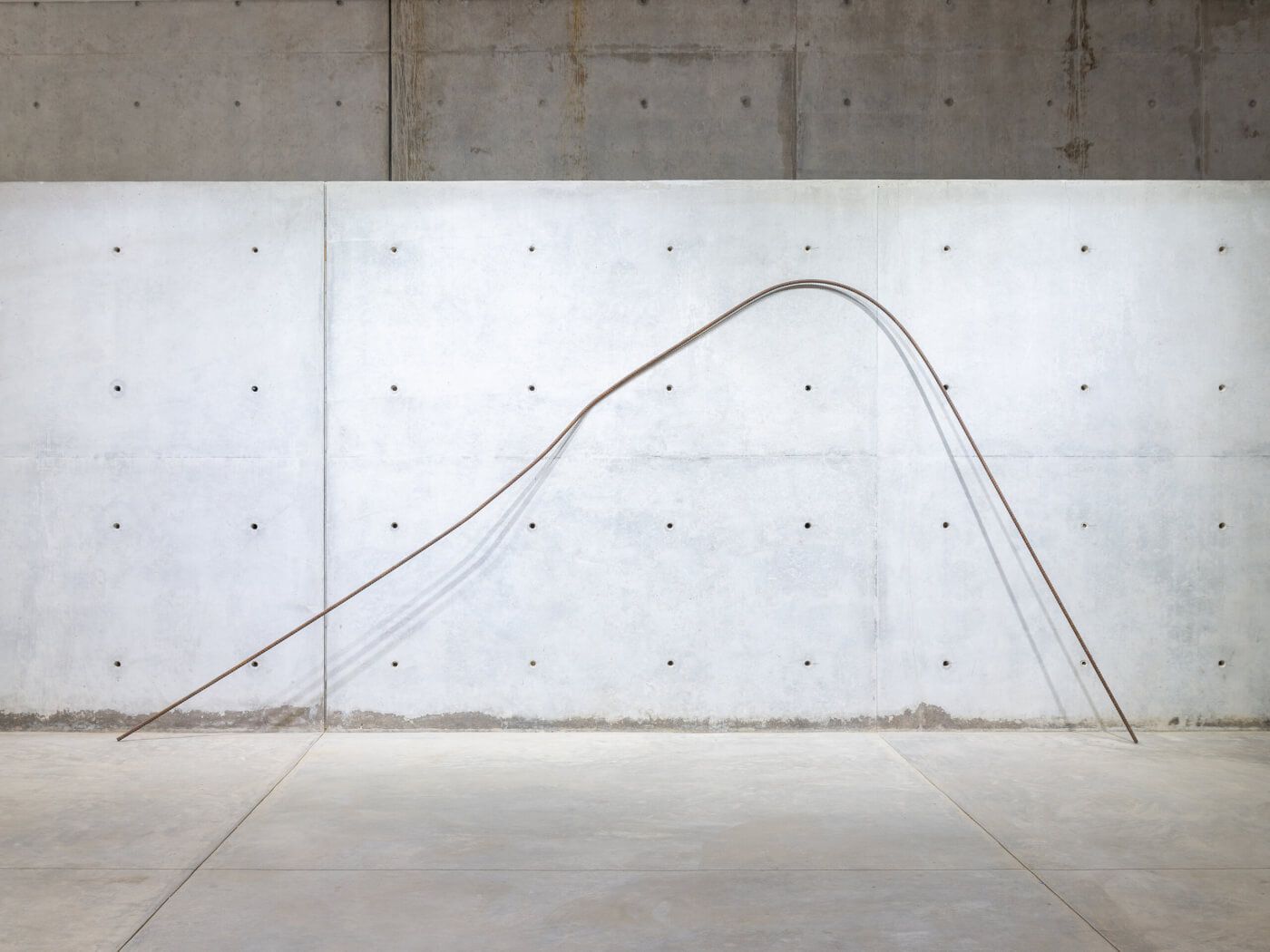

On another long wall, a single piece of bent rebar, also scavenged from a construction site but otherwise unchanged, becomes a drawing in space: a topographical memory, the afterimage of a mountain, or a template for the fabrication of a new one. The simplest of forms, and a counterpoint to the plywood stacks, it serves as a powerful reminder that the line separating our life in the natural environment versus our life in our constructed ones remains blessedly, or alarmingly, thin. Between these two implied spaces and states, Dávila has produced a whole spectrum of accumulated material experience spanning the stone age to the present day.

It can be hard at times to read past the characteristic seductions of seemingly formal sculpture. That Dávila’s work achieves uncanny, abstract beauties that need no explanation is one of its great strengths. But his sculpture is principally civic. What sets it apart from the work of the many artists who coax the sublime from scraps, including those who share his political intent, is Dávila’s determination to present webs of life in which we see and feel the interconnectedness and interdependence of systems/processes/materials, the needs they service, and the remains they leave behind. All of which he treats as shared culture: our collective memory in material form.

Dakin Hart

By accessing and manipulating memory through mundane construction materials—the current material franca of civilization—the works he has made for Casa Wabi generate a sense of communality. Not only because refuse everywhere looks much the same, but because today most human beings share the anxiety that stems from living in environments in a perpetual state of building and unbuilding. A pile of rock—to take an example that has changed little in many millennia—is a universally evocative metaphor of collective understanding because rock is so basic to our experience of the built environment. And just as rock can be almost endlessly reincorporated into new structures, so we are constantly reconfiguring our memories: drawn from our own experience, but also the experiences of those around us, and from our cultures and histories, into a continuously renovated social structure. Plywood, reinforced concrete, and rebar have, similarly, become inescapable parts of this terroir of modern life—trash that represents us all: a kind of repository of common experience.

The French philosopher and sociologist Maurice Halbwachs (1877–1945), one of the early theorists of collective memory, was good at suggesting how our delusions of separation and self-sufficiency might come to riddle the prescriptions and presentation of history. Because so much of what we experience, or think of, as the uniqueness of ourselves actually expresses the combined influence of the many groups of which we are members.

A personal state thus reveals the complexity of the combination that was its source. Its apparent unity is explained by a quite natural type of illusion. Philosophers have shown that the feeling of liberty may be explained by the multiplicity of causal series that combine to produce an action. We conceive each influence as being opposed by some other and thus believe we act independently of each influence since we do not act under the exclusive power of any one. We do not perceive that our act really results from their action in concert, that our act is always governed by the law of causality. Similarly, since the remembrance reappears, owing to the interweaving of several series of collective thoughts, and since we cannot attribute it to any single one, we imagine it independent and contrast its unity to their multiplicity. We might as well assume that a heavy object, suspended in air by means of a number of very thin and interlaced wires, actually rests in the void where it holds itself up….

Halbwachs does not say so explicitly, but one logical extension of this thinking is that collective memory is the seedbed of our sense of collective responsibility to each other and to our world. That is the source of much of Dávila’s interest in the idea.

For Casa Wabi Dávila has created works that are more settled, stable, and centered than his characteristic heavy objects suspended in the void. In a relaxed, spontaneous, and collaborative process not unlike the stockpiling of materials for later use, he has arranged: rebar and sheet steel; sections of the plywood and steel formwork used to cast concrete; rocks; and sections of scaffolding and I-beams, in four separate rough, large, open boxes on the floor. The boxes, recalling the empty geometries of minimalism, here serve as containers: post-industrial brain cases of a sort, filled with the gray matter of material history. Where his cantilevered, strapped, and suspended sculptures epitomize the vast and somewhat terrifying potential energy in social systems, these works are more like batteries or solid state drives, in which collective experience is stored. Also significant in these works is the way that entropy and decay, in returning them to a lower natural state, seems to have renewed them, rendering them ready for reuse. Their “chromatics,” as Dávila puts it, have thus come to “seem endemic” to Casa Wabi and this part of Oaxaca. Which is to say that if these materials represent a condition of shared memory, that condition now includes the environment as well.

Against one wall of the gallery are stacked sheets of plywood left over from, among other uses, the production of the cement pedestals in the exhibition. Arranged as they are, by the unconscious logic of temporary storage, they have a casual resemblance to a rough city skyline in silhouette. Or individuals in perspective-flattened queues. The pedestals, made to Dávila’s studio’s specifications for the display of sculptures, are outside on the terrace—arranged as sculpture. When he arrived to make the exhibition, Dávila treated them like the rest of the discarded materials that had been gathered for his use and pulled them into the flow of recycling and renewal that produced the art that is the exhibition. By placing them alone outside, as if they were sculpture, Dávila has opened up their status by inviting them to try something else and by giving nature the opportunity to turn them from (manmade) stone into rocks. It’s an accelerated, art-specific experiment in what has already happened to the materials shown inside. The gesture is typical of the universalizing culture of care Dávila tends to cultivate. The manmade materials expended outside come in to rest and recharge; those made for use inside go out for the same reason. It’s a lovely, non-binary exchange without judgment: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

On another long wall, a single piece of bent rebar, also scavenged from a construction site but otherwise unchanged, becomes a drawing in space: a topographical memory, the afterimage of a mountain, or a template for the fabrication of a new one. The simplest of forms, and a counterpoint to the plywood stacks, it serves as a powerful reminder that the line separating our life in the natural environment versus our life in our constructed ones remains blessedly, or alarmingly, thin. Between these two implied spaces and states, Dávila has produced a whole spectrum of accumulated material experience spanning the stone age to the present day.

It can be hard at times to read past the characteristic seductions of seemingly formal sculpture. That Dávila’s work achieves uncanny, abstract beauties that need no explanation is one of its great strengths. But his sculpture is principally civic. What sets it apart from the work of the many artists who coax the sublime from scraps, including those who share his political intent, is Dávila’s determination to present webs of life in which we see and feel the interconnectedness and interdependence of systems/processes/materials, the needs they service, and the remains they leave behind. All of which he treats as shared culture: our collective memory in material form.

Dakin Hart